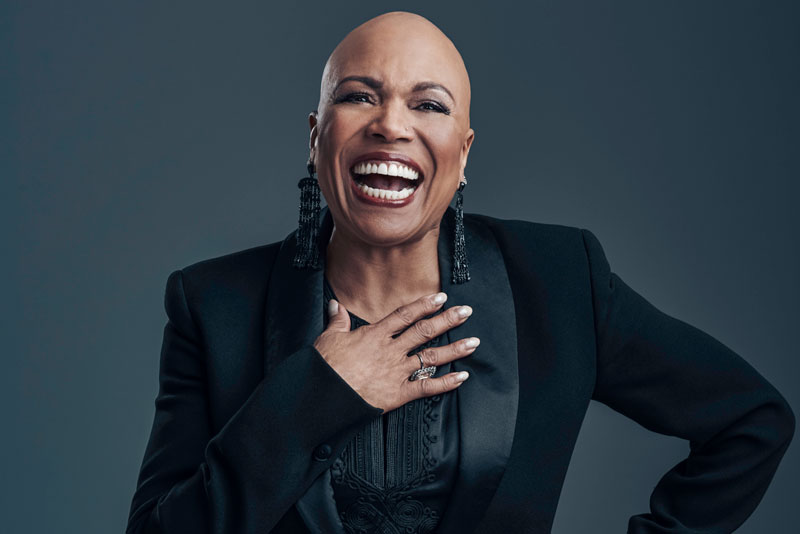

On a Thursday evening a few months ago, a long line snaked along Seventh Avenue, outside the Village Vanguard, a cramped basement night club in Greenwich Village that jazz fans regard as a temple. The eight-thirty set was sold out, as were the ten-thirty set and nearly all the other shows that week. The people descending the club’s narrow steps had come to hear a twenty-seven-year-old singer named Cécile McLorin Salvant.

In its sixty years as a jazz club, the Vanguard has headlined few women and fewer singers of either gender. But Salvant, virtually unknown two years earlier, had built an avid following, winning a Grammy and several awards from critics, who praised her singing as “singularly arresting” and “artistry of the highest class.”

She and her trio—a pianist, a bassist, and a drummer, all men in their early thirties—emerged from the dressing lounge and took their places on a lit-up stage: the men in sharp suits, Salvant wearing a gold-colored Issey Miyake dress, enormous pink-framed glasses, and a wide, easy smile. She nodded to the crowd and took a few glances at the walls, which were crammed with photographs of jazz icons who had played there: Sonny Rollins cradling a tenor saxophone, Dexter Gordon gazing through a cloud of cigarette smoke, Charlie Haden plucking a bass with back-bent intensity. This was the first time Salvant had been booked at the club—for jazz musicians, a sign that they’d made it and a test of whether they’d go much farther. She seemed very happy to be there.

The set opened with Irving Berlin’s “Let’s Face the Music and Dance,” and it was clear right away that the hype was justified. She sang with perfect intonation, elastic rhythm, an operatic range from thick lows to silky highs. She had emotional range, too, inhabiting different personas in the course of a song, sometimes even a phrase—delivering the lyrics in a faithful spirit while also commenting on them, mining them for unexpected drama and wit. Throughout the set, she ventured from the standard repertoire into off-the-beaten-path stuff like Bessie Smith’s “Sam Jones Blues,” a funny, rowdy rebuke to a misbehaving husband, and “Somehow I Never Could Believe,” a song from “Street Scene,” an obscure opera by Kurt Weill and Langston Hughes. She unfolded Weill’s tune, over ten minutes, as the saga of an entire life: a child’s promise of bright days ahead, a love that blossoms and fades, babies who wrap “a ring around a rosy” and then move away. When she sang, “It looks like something awful happens / in the kitchens / where women wash their dishes,” her plaintive phrasing transformed a description of domestic obligation into genuine tragedy. A hush washed over the room.

Wynton Marsalis, who has twice hired Salvant to tour with his Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, told me, “You get a singer like this once in a generation or two.” Salvant might not have reached this peak just yet, he said. But, he added, “could Michael Jordan do all he would do in his third year? No, but you could tell what he was going to do. Cécile’s the same way.”

Read the full article on The New Yorker

Cécile McLorin Salvant on TKA